When customers send robots to shop for them, how do you stop them from emptying the store?

Imagine you run security at a members-only warehouse retailer where access is restricted, prices are better than anywhere else, and some items are scarce, high-value, or released in limited quantities. For years, this was manageable. You checked membership cards at the entrance, recognized regulars, and could easily spot fake cards. You knew which members played by the rules and which ones caused trouble. Then one day, corporate tells you: “We’ve approved thousands of robot shopping assistants. They all look like and claim to shop on behalf of members. You need to make sure that none of them exploit the system. Figure it out.”

This is the current situation for many publicly facing websites and APIs as AI agents are starting to navigate the web and take actions on behalf of users.

Why the Bot Problem Potentially Just Got a Lot Worse: AI Agents

AI agents are now automating tasks that humans used to do themselves such as shopping, research, booking travel, and managing accounts. This is genuinely useful, but it’s also creating a massive problem for defenders.

Here’s the thing: good agents, legitimate users, and bad bots don’t look identical. Not yet anyway. The real problem is that we’re losing the signal that made detection possible in the first place. When real users browse the web, they bring natural entropy with them. Browser signals, cookies, query parameters, header structures, user journey patterns, IP infrastructure diversity, daily seasonality, etc. All of this feeds the fingerprinting and behavioral analysis systems Cequence has spent years building. A human browsing a shopping site looks different from a bot because humans are messy, inconsistent, and unpredictable in a statistically significant way.

Agents don’t have that natural entropy. They aren’t browsing in a traditional sense, for the most part don’t look like a real browser, and don’t provide a differentiable signal that allows for the blocking of abusive traffic prior to the detection of abusive behavior.

From our analysis of retail traffic over the past six months, the overwhelming majority of self-announced AI traffic is still training crawlers, the large-scale scrapers feeding data to models like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini. Actual AI agent traffic (agents taking actions on behalf of users) is still a small percentage, but it’s growing. And with Google’s recent announcement of the Universal Commerce Protocol (UCP) for agentic shopping, backed by major players in the space, this isn’t theoretical anymore. It’s happening now.

When “Trusted” Traffic Can’t Be Trusted

Let’s go back to our warehouse for a second. You’ve allowed helpful shopping robots inside. They grab items for members, speed up checkout, and reduce congestion. Members love them for their convenience and management loves the increased volume, but now two new problems have emerged.

Problem 1: Spoofing (The robot costume)

Let’s envision one novel avenue for abuse in this post-robot shopper world. A known bad actor, previously banned on sight at the store, sees the new robot foot traffic entering the store. They “borrow” one of these robots and make a convincing robot costume, then waltz right into the store and pick right back up with their abusive behavior, buying out limited quantity items or doing price analysis for a competitor. In technical terms, attackers copy the exact structure of legitimate agent traffic. If the robots are basic enough in structure to create convincing costumes for, the same bad actor could continue to come back and disrupt the business with their abusive behaviors again and again, with security needing to wait for the abuse to start before being able to take action, which in many cases would be too late. Without a way to verify legitimate robots or differentiate between them and the robot disguises, your security team would be up the proverbial creek without a paddle.

Problem 2: Reflection and Tunneling (The compromised shopping robot)

In this case, the attacker doesn’t need to make a robot costume, they can trick a legitimate shopping assistant into following their malicious instructions. This is worse, as there is now no way for the security team to tell the difference between a costume and a robot as a layer of defense. Without proper accountability for both the robot manufacturer and the shopper who it is claiming to represent, your team would again be forced to wait for abuse to occur before being able to stop it. This pattern already exists today outside of AI agents, where attackers abuse trusted intermediaries to make requests on their behalf. When traffic originates from a well-known or allow-listed service, traditional defenses can be completely bypassed.

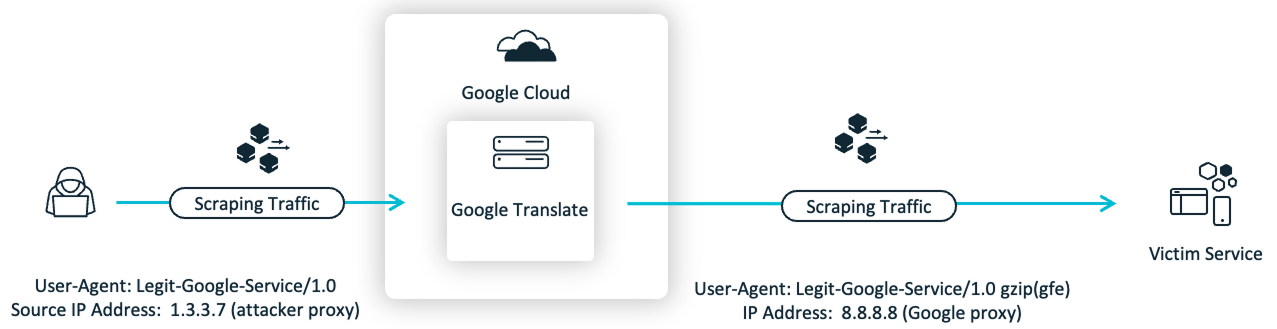

A Real-World Example:

We’ve already seen this pattern in the wild outside of the context of AI Agents, through a scraping attack that abuses a Google Translate service. Here’s how it works: they submit a URL to Google Translate, and Google’s servers fetch the content on their behalf. The requests genuinely come from Google’s IP ranges with legitimate-looking spoofed User-Agent strings. Attackers have reflected their scraping traffic off the Google Translate service, gaining characteristics (the source IP address) of a legitimate and potentially allow-listed service. Even worse, the way that the service is coded allows attackers to send custom spoofed User-Agent strings that can mimic legitimate Google automation User-Agents (this has been already reported to Google), with the service itself making minimal modifications to the attacker-controlled User-Agent. Why is this an especially insidious attack? IP infrastructure combined with User-Agent announcement is the recommended standard for how to recognize “good bot” traffic.

Though in this case Cequence threat researchers were able to find subtle differences between attack and legitimate traffic, as well as flag the anomalous scraping behavior to begin with, one can easily see how an attack like this could potentially leave defenders with an impossible choice: block all robot traffic and lose the legitimate business benefits, or allow it all and accept the abuse. Neither option is preferable.

This example of reflection is of slightly lower consequence as no actions are being taken, page content is just being fetched/scraped, and odds are the primary way users are interacting with your site is not Google Translate. The potential consequences of reflection or spoofing are far worse if the service in question is one of the primary ways users interact with your application, e.g. the coming wave of Agentic AI traffic.

The Solution: Verifiable Identity for Bots (and Their Users)

What if every robot had a cryptographic ID card that couldn’t be forged?

This is exactly what the Web Bot Auth standard proposes. It’s being developed by an IETF working group and builds on HTTP Message Signatures (RFC 9421). The concept is straightforward:

- Bots sign their HTTP requests with cryptographic keys

- Receiving servers verify those signatures against published public keys

- If the signature checks out, you know the request genuinely came from who it claims to be

The good news is that adoption is already underway. OpenAI’s Operator product already implements this. Major edge providers can already verify these signatures at the edge.

But here’s the catch: operator identity alone isn’t enough.

Let’s say OpenAI becomes the dominant agent platform; currently 80% of agentic traffic flows through them. Great, now all that traffic is verified as “from OpenAI.” But we’re back to square one: it all looks the same. When abuse happens, what do you do? Block all OpenAI traffic? That’s the nuclear option. And OpenAI is now stuck fielding millions of abuse reports with no way to attribute bad behavior to specific users. Another twist is that different organizations may consider different behaviors abusive or be more or less strict with traffic hitting their site. Many AI Agents don’t even need help misbehaving, as being non-deterministic means unpredictable behavior is part of the design. The bot provider becomes both a major single point of failure and is faced with an incredibly tough challenge of determining what actions or behaviors are considered abusive for every individual service or API they interact with.

User-Level Identity in the Same Framework.

The good news: Web Bot Auth’s architecture is already flexible enough to support this. The Signature-Input header can include custom parameters and sign additional headers. Here’s how it could work in practice:

- User authenticates with the agent platform (you already log into ChatGPT, for instance)

- When the agent makes requests on your behalf, the platform includes a user identifier (could be pseudonymous, doesn’t need to be PII)

- This user ID gets cryptographically signed alongside the agent identity

- Receiving servers can now attribute requests to both the agent AND a specific user

The platform maintains the mapping between pseudonymous ID and real user. When abuse reports come in, the bot provider can action the actual account. Additionally, when abuse happens, the same behavioral detections that have been honed over years can detect and mitigate anomalous user behavior with the granularity of the end users themselves. More on this later.

Why does attribution matter?

- It discourages misbehavior. If users know their identity is attached to agent actions, they’re less likely to authorize abuse in the first place.

- It enables granular enforcement. When abuse happens, platforms can action specific users rather than blocking entire agent populations.

- It scales abuse reporting. A dominant platform can handle fraud reports by user, not just by “it came from our system somewhere.”

The industry should push for standardized user identity parameters within Web Bot Auth, not a patchwork of separate protocols. The architecture supports it. We just need to agree on the implementation.

A note on the privacy tradeoff. Yes, this creates a linked chain of identity. If you use the same agent platform across multiple sites, your activity could theoretically be correlated via that pseudonymous ID. But this is arguably the point for abuse prevention, and it’s no worse than cookies or IP tracking today. If privacy becomes a major concern, platforms could offer per-site pseudonymous IDs to limit cross-site correlation. The key is that the user identity doesn’t have to be PII exposed to the receiving server; it just needs to be consistent enough for the agent provider to action abuse reports, and for the application to track abusive behavior and user journeys. The platform holds the real mapping, not the websites you visit.

Shouldn’t site specific user/session handling already cover this? The critical thinker may note that many services already implement their own user identities and track user sessions. Why is this addition of AI platform user ID necessary? The answer, many online services can be operated anonymously or by using a “guest” account. Another consideration: what happens when AI Agents start creating accounts on behalf of their users? My argument is that there are many instances whereby AI automation can act as an anonymizing layer when it should not.

A Warehouse That Adapts

The retailers that modernize their security systems will thrive. Those that don’t will fail in one of two ways:

- Lock out robot shoppers entirely and lose legitimate business

- Let everyone in and watch shelves get stripped bare or competitors steal market share

Robot shoppers aren’t replacing today’s threats; they’re adding to them. Traditional bot abuse still dominates web and API traffic in terms of volume. AI agents just add a new layer of complexity. Meanwhile, legitimate automated commerce represents a massive opportunity. The retailers that can tell helpful shopping assistants from scalpers and spies will capture it. The ones that can’t will bleed inventory and margin. Agentic assistants are coming. The question isn’t whether to let them shop, it’s whether you’ll know which ones to trust.

For assistant creators (AI agent providers)

Adopt Web Bot Auth now. Push for user-level identity parameters and your own abuse management will thank you when you’re the dominant platform fielding millions of fraud reports. Good assistants should come with ID cards. Responsible assistant production means being able to stand behind your agents and their users.

For retail warehouse owners (enterprises and platforms)

Start requiring verifiable identity for automated traffic. Put pressure on agent providers to implement cryptographic verification. Invest in behavioral analysis that can adapt to agent-based traffic patterns. You can cater to the new assistant customer base and protect yourself, but only if you have both the ID system and the vigilance to back it up.

The robots are coming. The question isn’t whether to let them in but how you’ll know which ones to trust.

Contact us today to learn how Cequence can help securely enable agentic AI in your organization to enhance revenue and unlock internal productivity.